History professor Jonathyne Briggs’ personal journey leads to an upcoming book on the history of autism in France

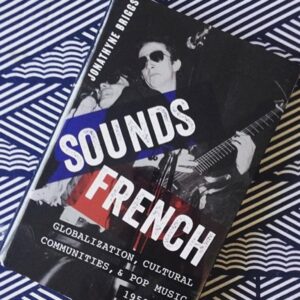

When Jonathyne Briggs was planning a 2014 trip to France to do research for his book Sounds French: Globalization, Cultural Communities, and Pop Music, 1958-1980, he considered whether his children — including his seven-year-old son Sean, who has autism spectrum disorder (ASD) — could travel with him.

“When I looked into it, I realized not only could I not make it work, but that the understanding of Autism in France is radically different than we see it here in the states, especially in terms of treatment expectations,” he said.

The Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy Sean (who is now 16) received in the U.S. was not the standard in France. Briggs, a history professor who teaches multiple contemporary European history courses and a course on the history of disability at Indiana University Northwest, began to investigate the cultural reasons for the differences, past and present.

After eight years of exploration, he is currently writing a book for Oxford University Press on the subject, which he expects to be published in late 2024.

“I was looking for a new topic, and this was very personal to me,” he said. “I thought it was the right time to write it.”

A history lesson

When autism was first identified in the 1940s, says Briggs, “the assumption was that autistic children were just expressing bad behavior that was a reaction to negative parenting — that it was the mother’s fault… This was true in the United States, as well as in France, which is a very patriarchal society.”

As parent advocacy groups pushed the medical establishment to evolve its views, new methods of treatment, like ABA, emerged in the U.S.

But the belief that autism is “a defensive reaction to parents treating a child badly — emotionally or physically” endured into the 21st century in France, says Briggs, where psychoanalysis remains the prevailing form of treatment.

In a 2022 publication for Cambridge University Press, Briggs explores the ways that parents have pushed back in France, but advocacy for children and adults with autism remain behind the U.S.

“The recognition of autism as a disability… the right to education, the right to inclusion, the right to employment and the need for greater support for what we call special education — while we may fight about these things in the United States, I would argue that there is still at least some recognition that those rights have social value,” Briggs said. “But in France, the debate on that is a little further behind. The advocacy has taken longer to take root.”

Changing perceptions

Briggs is also examining the perception of autism as a childhood disorder, which is perhaps a side effect of parents continuing to be so instrumental in shifting medical and societal attitudes.

“Something I'm interested in exploring in the book is why we think of autism as something associated with children,” says Briggs. “I think about my own child who will be moving into a group home with other boys his age. He is growing up and is going to go and have his own life, but he will always be autistic.”

When Briggs returns to France for further research on the new book, he is hoping to do more than complete his archival research. “I don’t want to just tell the story of parents. I don’t just want to tell the story of doctors — I am trying to figure out ways to tell the story of Autistic people as well,” he says.

He hopes to speak to individuals with autism who participate in self-advocacy groups. “I want to ask them ‘what is not in this story that needs to be told?’ That will make this a much better book, and a more durable one.”

Briggs has seen the way that published research can meaningfully move discussion. He appreciated the way the uncovered terrain he explored for his book Sounds French opened new avenues of dialogue in the field of Modern European History.

His wish is that his upcoming book will do the same, and that it will be translated into French.

“My hope is my book leads to other books… I am trying to open up the conversation,” he said.